Secure desktop login with a one-time token

The usual desktop login using a username and password provides some rudimentary security against unauthorized access, but it's not always enough. Users often use weak passwords and even write them on a sticky note placed on their monitor. You don't need to be a security expert to realize that unauthorized logins under such circumstances are not that hard.

Other authentication methods that provide an additional step are much more secure. One approach is generating unique one-time-use tokens – password-like strings – that provide an extra level of security. The computer requests the one-time password (OTP) at login together with the other credentials.

The secret is that only an authorized user has access to the one-time token. Unauthorized third parties (e.g., colleagues) can't get the OTP and, therefore, cannot log in. These methods are also referred to as two-factor, or two-step, authentication.

Google Helps

Two-factor authentication is done on Linux systems mostly with a Pluggable Authentication Module (PAM) module – as in this case with a desktop login extension. You can get a simple but powerful solution from Google. With the help of the Google Authenticator [1] you can extend the PAM used for login to the Linux machine by mounting an additional library. PAM software libraries provide a common API for authentication services. So, rather than creating the login details for each program, PAM provides a standardized service in the form of modules.

On your Android, iOS, or Blackberry smartphone, you also can install a free app [2] that links the Linux login with the Google Authenticator. When the system prompts you for the time-based, one-time password (TOTP), you can then grab the smartphone and read the string off it.

Note that both the smartphone and the Linux computer require a working time synchronization. If the times drift apart, the TOTP login won't work. The Google Authenticator mechanism also doesn't necessarily have to apply to all the users of the system: PAM can be configured so that it won't lock out other users.

Five Minutes

For the test installation, I used Ubuntu 14.04 (32-bit). Unless otherwise indicated, all commands must be executed using root privileges. If you're not on Ubuntu or one of its derivatives, you'll find helpful tips and tricks for two-factor authentication on the Google Authenticator project wiki [3].

To begin, you need to get the system up to date using apt-get (Listing 1, lines 1 and 2), then configure the required components from the repository (line 3). In my test, the necessary package, libpam-google-authenticator , was in the official Ubuntu repo. The package can go by a different name in other distributions.

Listing 1

Update and Configure

$ sudo apt-get update $ sudo apt-get upgrade $ sudo apt-get install libpam-google-authenticator libqrencode3

You might also need the libqrencode3 package for an extra measure of comfort. The library allows Google Authenticator to generate a QR code, which you scan in with your smartphone and link to your account with Google Authenticator, as described later.

The next step is to build the Authenticator into the login screen that appears at system startup. On Ubuntu 14.04, open the PAM configuration file of the LightDM display manager (/etc/pam.d/lightdm ) with a text editor and add the following line at the end:

auth required pam_google_authenticator.so nullok

The nullok parameter at the end ensures that logins from other users remain possible without Google Authenticator.

If you also want the screensaver to have a token when unlocking it, add the /etc/pam.d/gnome-screensaver file reference to the configuration file. If you're not using LightDM or the Gnome screensaver, make the adjustment to the display manager and screensaver of your system. Note that my test was exclusively with Google Authenticator on stock Ubuntu.

Token, Token, Token….

Next, enable Google Authenticator for the desired user account. The Google Authenticator app first must be installed on your smartphone. Open a terminal in Linux and enter the command google-authenticator as your regular user (not root!). The application recommends various configuration options, and you can decide which one works best for you.

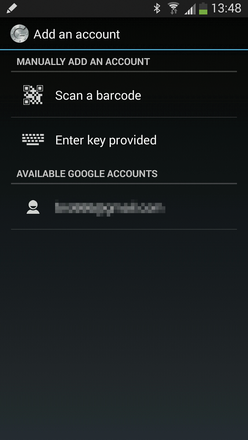

The tool describes all configuration values. I answered the first prompt with Yes, after which Google Authenticator spits out some QR code (Figure 1). Next, open the app on your smartphone (Figure 2) and scan in the QR code (Figure 3). In this way, you link the Linux login with the Google Authenticator.

Figure 1: The Google Authenticator generates the required data and prepares the QR code for scanning.

Figure 1: The Google Authenticator generates the required data and prepares the QR code for scanning.

Figure 2: After first opening the Google Authenticator app on your smartphone, Google lets you scan a bar code.

Figure 2: After first opening the Google Authenticator app on your smartphone, Google lets you scan a bar code.

Figure 3: Scanning in the QR code is a cinch and lets you link the Linux login to the Google Authenticator..

Figure 3: Scanning in the QR code is a cinch and lets you link the Linux login to the Google Authenticator..

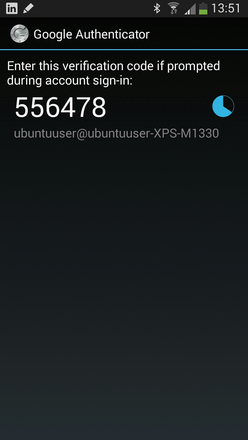

The app acknowledges it by giving you a one-time code (Figure 4).However, that doesn't end the setup just yet. The Authenticator then poses further questions to which you can respond at your own discretion. I opted to answer all of them with y . A view of the completed configuration appears in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Google Authenticator confirms the successful linking process by showing a one-time passcode.

Figure 4: Google Authenticator confirms the successful linking process by showing a one-time passcode.

Emergency scratch codes appear when responding to questions. You can use these to log in to the computer if the smartphone isn't handy, if the app isn't working, or if the system clocks between computer and smartphone are off. Write down these single-use tokens and store them in a safe place away from your computer.

Trust Is Good

Now that setup is completed, you can put your system through some tests. In principle, it's enough just to log off. However, because you upgraded at the beginning of the setup, you might as well restart the computer.

At the next login session, the system asks for a one-time token along with the usual username and password (Figure 6). Open the smartphone app and enter the indicated token in the login field. Remember, however, that the one-time password is only good for a limited time. Fortunately, generating the TOTP works even when the smartphone is offline.

Figure 6: You use the code delivered by your smartphone to log in after entering your username and password.

Figure 6: You use the code delivered by your smartphone to log in after entering your username and password.

Conclusion

Securing a desktop login using a two-factor authentication approach requires only a very simple setup but provides a great deal of additional security. The Google Authenticator proves to be a useful and handy tool when it comes to accessing and entering the TOTP.

Even more secure are solutions based on hardware tokens, such as YubiKey [4] from Yubico [5], but they come with significant financial and setup cost. l

Infos

- Google Authenticator: http://code.google.com/p/google-authenticator/

- Google Authenticator app: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.google.android.apps.authenticator2&hl=en

- Google Authenticator wiki: https://code.google.com/p/google-authenticator/wiki/PamModuleInstructions

- Getting started with Yubikey https://www.yubico.com/start/

- Yubico: http://www.yubico.com